Grades 8-11

Triangle Theory Building: Key Episodes

These are scripted scenarios based on what actually happened when this module was run at two schools in India. They are written as teacher-ready dialogues so you can see what the conversations look like in practice, what went well, what went poorly, and what to do differently.

Student names are real first names from the implementation. The letter T refers to the teacher.

Episode 1: The Equilateral Proof

Context

This is the first proof of the module. The class has just finished listing their claims about triangles on the board. The teacher picks claim 4: "The angles of an equilateral triangle are equal." This episode happened at Ganga (School 1), in the first session.

The dialogue

T: Let us pick up claim 4: the angles of an equilateral triangle are equal. Why should I believe that? Can you try and show that is true using other things written on the board?

Time for group discussion. After a few minutes, the teacher asks the middle group to present.

Arnav comes to the board and draws an equilateral triangle.

Arnav: We have an equilateral triangle. All the sides are equal and so this is also an isosceles triangle. So, this angle and this angle are equal. If we consider this vertex, this angle is equal to this angle, and all the angles are equal.

Pankaj (interrupting): Angles opposite equal sides are equal.

The teacher writes up the proof:

Equilateral triangles have equal sides

Angle A = Angle B since CA = BC (by: angles opposite equal sides are equal)

Angle C = Angle B since AC = AB (by: angles opposite equal sides are equal)

So, Angle A = Angle B = Angle C

T: Just because Angle A = Angle B and Angle B = Angle C, why does Angle A = Angle C?

Vivaan: If we say that if something is equal to something else and something else is equal to something other than that, then the original thing will equal to that. If we work like that, then this follows.

Vivek: A is equal to B, so in the place of B you can put A.

The teacher accepts this and moves on.

What the teacher did well

- Insisted on writing the proof out step by step on the board rather than accepting a verbal summary

- Caught the implicit use of transitivity ("just because A = B and B = C, why does A = C?") — this is exactly the kind of hidden assumption that assumption digging is meant to surface

- Let Arnav present in his own words rather than correcting immediately

What the teacher could have done better

- Vivaan's response — "if we work like that, then this follows" — was the first time a student explicitly framed something as an axiom (a rule we agree to use). The teacher did not fully parse this in the moment and moved on too quickly. In retrospect, it would have been worth pausing: "Vivaan, you said 'if we work like that.' You are proposing a rule. Can you state the rule?" This would have been the first explicit encounter with axioms, much earlier in the module.

What to do differently

When a student says something that amounts to proposing an axiom or a rule of reasoning, stop and name it. "You are saying: if A equals B, and B equals C, then A equals C. This is called transitivity. Notice that we are choosing to accept this — it is a rule we agree to use." This sets up the axiomatic ideas that come later in Session 3.

Episode 2: The Classification Debate

Context

This episode happened at Indus (School 2), in the first session. The students had listed "4 types: equilateral, right angled, scalene and isosceles" as one of their claims. The teacher starts by pointing out the inconsistency in the classification criteria.

The dialogue

T: You mentioned various different types of triangles. If we were to classify triangles, would you classify them like this?

The teacher draws a tree with "Triangle" at the top and all four types directly below it.

Tarini: See, there are two types of classification, one is to do with the sides and another is to do with the angles.

T: Yeah. So, let's stick to the sides for now. What are the different types?

Multiple students: Equilateral, isosceles and scalene.

The teacher draws a tree with "Triangle" at the top and the three types below it.

T: Now if we prove something about isosceles triangles — that angles opposite equal sides are equal — then it's not true about equilateral triangles?

Multiple students: It is.

T: But equilateral triangles are not types of isosceles triangles.

Multiple students: They are.

Devika: Equilateral triangles are a type of isosceles triangle but every isosceles triangle is not an equilateral triangle.

The teacher redraws the tree with equilateral under isosceles. But then:

Multiple students (led by Tanya and Tarini): You have scalene, then isosceles, then equilateral.

T: So, isosceles triangles are types of scalene triangles?

Multiple students (including Tarini and Tanya): Yes.

T: So, what is the meaning of scalene triangles?

Uday: A random triangle is a scalene triangle.

T: But an isosceles triangle is a scalene triangle?

Multiple students: Yes.

T: So, all triangles are scalene triangles?

Multiple students: Yes.

T: So, what is the difference between the word triangle and scalene triangle?

Multiple students: Nothing.

Tanya: All triangles do not come under isosceles or equilateral. So, there should be another category.

T: That's just a triangle.

Tanya: But, every triangle is not isosceles or equilateral.

The teacher draws a Venn diagram with a large circle for triangles, a smaller circle inside for isosceles, and a smaller circle inside that for equilateral.

Tanya: We should have a name for the part remaining. So, that is scalene.

T: But you said that is not scalene. You said the whole thing is scalene.

Tanya: Yes.

What the teacher did well

- Let the contradiction develop naturally rather than correcting it immediately. The students walked themselves into the "scalene = triangle" trap, which made the problem vivid.

- Used the Venn diagram as a different representation to test whether the confusion was about the tree notation or the underlying logic.

What the teacher could have done better

- The competing values (logical inheritance vs descriptive labelling) were never made fully explicit. Tanya wanted both: she wanted scalene to be the parent category (for logical inheritance) and also wanted scalene to name the leftovers (for description). These are incompatible goals. Stating this tension explicitly would have helped: "You want two things at once. You want a name for the triangles that are not isosceles, and you want a nesting where everything inherits. You cannot have both with the same word."

The 47.5-degree challenge

Later in the same session, the teacher posed this question about the angle-based classification:

T: I can add another category of triangles with one angle equal to 47.5 degrees. Why is this a bad classification while the right-angle one is good?

Uday: Most probably we won't have a triangle which is 47.5 degrees.

T: Most probably, you won't have a right angle triangle. So, what is it about right angled triangles?

Prerna (along with others): a squared plus b squared equals c squared.

Devika: The square of the hypotenuse equals the sum of the squares of the other two sides.

T: So, you know a lot of things about right angled triangles. This is useless. You know nothing about 47.5 degree triangles which you do not know about 50 degree triangles.

What to do differently

The analogy from biology (red socks vs age) is worth spending more time on. Draw it out: "In biology, classifying humans by sock colour is useless — there are no biological correlations. Classifying by age around adolescence is useful because real biological changes cluster there. In geometry, the same principle applies: we classify by right angles because theorems cluster there."

Episode 3: The Congruence Tangle

Context

This episode happened at Ganga (School 1), in a later session. The class had been working on the isosceles triangle theorem (angles opposite equal sides are equal) and the proof used RHS congruence. The teacher wanted students to see the equivalence between different congruence tests.

The dialogue

T: How do you know that RHS gives you that the triangles are congruent? What do you mean by congruence?

Sana: The triangles are equal.

Gauri: They coincide.

Sana: When kept one on top of—

Imran: Overlap.

Vivaan: If we rotate or move or reflect the triangle, then they coincide. Using only these three operations.

T: So what you are saying is that SSS shows congruence and you are telling me RHS shows congruence. So, in some sense, at least when we are restricted to right angled triangles, there is this relationship: RHS is true if and only if SSS is true.

Sana: No, only two sides.

T: No, you're telling me that if you had RHS — the right angle, hypotenuse and side were true — you also get the third side is equal. And therefore you get that if this is the case, then this is the case. SSS implies RHS — that's straightforward, right? If all three sides are equal and it's a right triangle, you obviously have RHS. So, why does RHS imply SSS? Spend a minute thinking about that.

After group discussion:

Imran: So, by Pythagoras' Theorem, we could get the third side as well. And we know the equation is going to work for both the triangles. If two of the sides are the same, then the third side should also be the same.

T: Okay, so if this is c, this is a, then this is the square root of c² - a² and this is the square root of c² - a². So, there you go.

Anya: But if we have just the triangles and we don't know the measures?

T: You know that this is equal to this, right? We don't know the measures. We know that this is equal to this. Just call it c.

What the teacher did well

- Started from the conceptual question ("what do you mean by congruence?") before moving to the technical question about specific tests

- Imran's use of Pythagoras' theorem to derive the third side from RHS was a genuine student insight — the teacher wrote it out clearly on the board

What the teacher could have done better

- The teacher was imprecise with the word "true" — saying "RHS is true" when meaning "the RHS conditions are satisfied." This is exactly the kind of imprecision the module is supposed to help students avoid. Model the precision you are asking for.

- Anya's question ("But if we have just the triangles and we don't know the measures?") suggests she may have misunderstood the goal. She might have been thinking "how do we check whether two specific triangles are congruent?" rather than "given that two triangles satisfy RHS, show they also satisfy SSS." The teacher could have probed: "What do you mean? We are not measuring anything — we are assuming that the hypotenuse and one side are equal, and showing that the third side must also be equal."

- There were opportunities for students to justify easy claims (like SSS implies RHS in a right triangle) that the teacher did himself instead.

What to do differently

Be explicit about what you are doing: "We are not asking whether specific triangles are congruent. We are asking whether different ways of testing for congruence are equivalent — whether knowing one set of conditions guarantees the other." Write this goal on the board before starting.

Episode 4: The Straight Line Circularity

Context

This episode happened at Ganga (School 1), in the last session. The class had used the term "straight line" many times in the module without defining it. The teacher asked what a straight line is.

The dialogue

T: What is a straight line?

Gauri: A set of collinear points.

T: A straight line is a set of collinear points. What does collinear mean?

Vivaan: Collinear lies on a line. So, we will use straight line in the definition.

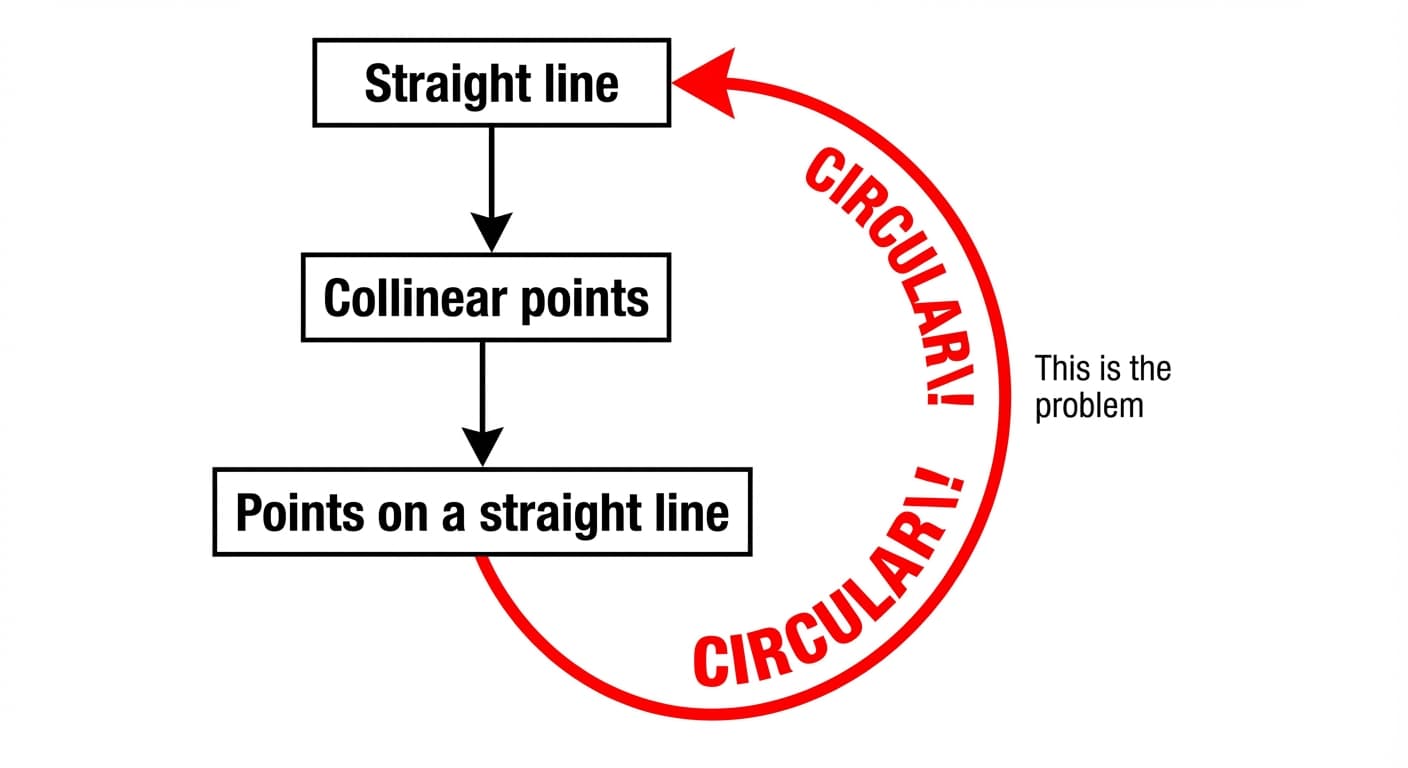

T: Points on a straight line. So, notice the problem with this. You define straight line as collinear and collinear as straight line. You see that being a problem, right? Circular.

The teacher draws the circularity on the proof tree — an arrow going back upward, forming a loop.

T: Remember the diagrams we have been building? It is okay if you use straight line in things which are in different branches of the tree. But in the same branch, if you use it and then use it again, that is a problem. Because that means there is circularity.

Imran: Can we use shortest path?

T: So, you want to use shortest path. What does this rely on?

Vivaan: What is a path?

T: One is "what is a path?" What else does it rely on?

Vivaan: What is shortest?

T: So, what is length? What do you mean by length? What is the distance between two points?

Imran: Maybe the points between them.

Vivaan: In Euclidean Geometry, then all lines will have equal length. See, there is an infinite number of points between two and there is also infinite between these two.

T: Yeah. So, shortest path requires distance. And distance is the length of the straight line. So we are back to straight lines again.

Pause. Then:

Gauri: What if we consider collinear points as the axiom? We do not have to further define it.

T: So, you don't want to further define collinear. Sure, you can do that. But you need something to tell me what collinear points are, right? Because why are these points not collinear? (draws three non-collinear points)

Gauri: Because they are not joined together by a straight line.

T: Can you think about it without using straight lines?

The teacher then gives an analogy:

T: Think about defining a t-shirt. Whatever words you use, I can keep asking you what you mean. With real objects, at some point you can point at the thing. In mathematics, you cannot point — the lines we draw are representations, not actual mathematical lines. So we have to treat certain objects as undefined and put rules on them called axioms.

For example: "Given two points, there is a unique straight line which they lie on." This does not tell us what a straight line is, but it constrains what the term can refer to.

What the teacher did well

- Let the circularity emerge from the students rather than pointing it out in advance. Vivaan spotted it himself: "we will use straight line in the definition."

- Made the circularity visible on the proof tree, showing it as a structural problem (a loop) rather than just a logical error

- The t-shirt analogy for undefined entities was clear and effective

What the teacher could have done better

- Gauri used the word "axiom" to describe what was actually an undefined entity. The teacher avoided the terminology rather than clarifying the distinction. In mathematics, "axiom" and "undefined entity" are different things: an axiom is a statement we accept without proof, while an undefined entity is a term we use without defining. The axiom constrains the undefined entity. It would have been worth saying: "You are suggesting that we leave 'straight line' without a definition. That makes it an undefined entity. The axiom is the rule we put on it — like 'given two points, there is a unique straight line they lie on.'"

- The teacher put words in Imran's mouth when he said "distance is the length of the straight line." It would have been better to push Imran to define distance himself and let the class discover the circularity.

What to do differently

This episode came at the very end of the course, which meant there was no time to develop the ideas about axioms further. If possible, get to this point by the middle of Session 3 so there is time to discuss: What other axioms might we need? What happens if we change the axioms? (This connects to Tanya's earlier observation about spherical geometry.)

Episode 5: The Altitude Dead End

Context

This episode happened at Indus (School 2). The teacher chose to discuss "the altitudes of a triangle meet at a point" because some students (Tarini and Tanya) had expressed interest. The teacher had a proof in mind using parallelograms and perpendicular bisectors that he planned to share if students got stuck, then have them dig into the premises.

The dialogue

T: That's kind of surprising, right? Because it wouldn't be surprising that two altitudes meet at a point — two lines meet at a point is not that surprising. The surprising thing is that the third passes through the same point. So, why?

Meghna: That's a theorem.

T: Why is that a theorem? So, altitudes of a triangle are these perpendiculars we drop from the top to the bottom, right? That two of them meet at a point is not surprising. But that the third passes through the same point is what is surprising.

Uday: They were not altitudes. They were perpendicular bisectors.

T: No, this is not a perpendicular bisector.

Uday: No. You have drawn it in a way that they are perpendicular bisectors.

T: So you think altitudes don't meet at a point?

Uday: Not altitudes.

T: But, everyone else is saying that altitudes always meet at a point. Do you think altitudes always meet at a point? (to the whole class)

Multiple students: Yes.

Uday: Sorry I got mixed up.

Later:

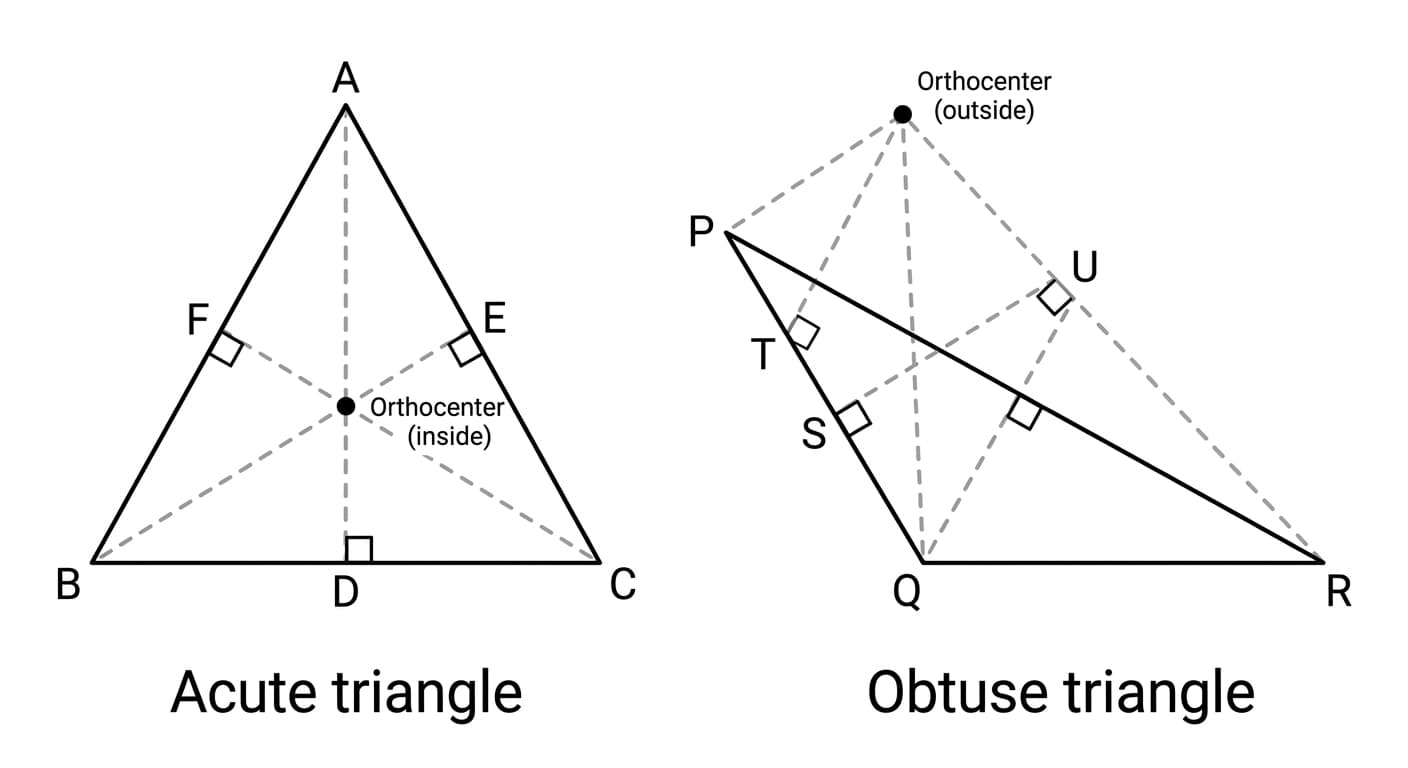

Devika: If there is an obtuse angle triangle, then the altitudes won't meet.

Tarini: They will.

T: That's a good point. (Draws an obtuse triangle.) This altitude is easy. Where is this altitude? (points at another vertex)

Devika: It will be outside.

T: So, you are saying you have to extend it.

Devika: But they are not meeting. Or are they?

Tarini: So, if you extend it, then it will meet.

The teacher gives this as a group task. After discussion, Varun comes to the board with a proof using cyclic quadrilaterals. The proof assumes a quadrilateral is cyclic, which Varun cannot justify without circularity:

T: How did you come to the conclusion that this is a cyclic quadrilateral?

Uday: Because we have proved that when two angles are subtended—

T: You know that if it was a cyclic quadrilateral, then those angles are equal, right? But how do you know it is a cyclic quadrilateral?

Uday: We are using the same thing.

T: No. You used the cyclic quadrilateral to show me that this equals this. Now you can't use this to show me that it is a cyclic quadrilateral.

The class spent more time trying to justify that the quadrilateral was cyclic without success. The teacher eventually moved on and later gave the students the proof he had originally prepared.

Why this episode did not work

As the teacher wrote in his notes: "This episode did not help all that much in achieving the goals of the module. The goal of the module is not that students learn Euclidean Geometry. Rather, it is that students learn to build theories."

The problem was that the initial proof of the claim was too hard for students to produce. They got stuck on the proof itself, and the session turned into a struggle with geometric content rather than an exercise in assumption digging. The assumption digging — working through the premises of a proof — requires having a proof in the first place.

What the teacher did well

- Handled Devika's objection about obtuse triangles well, working through a concrete example rather than polling the class

- Caught the circular reasoning in Uday's use of cyclic quadrilaterals

What the teacher could have done poorly

- Handled Uday's initial objection ("you have drawn it in a way that they are perpendicular bisectors") by polling the class, which may have pressured Uday into accepting the claim rather than genuinely resolving his concern. A better approach: "Draw some triangles on a piece of paper. Drop the altitudes. Do they meet at a point?"

- Assumed all students believed the claim without checking

What to do differently

If you want to discuss altitudes meeting at a point, give students the proof from the outset and then have them dig into its premises. The value of this module is in the digging, not in producing the proof. Alternatively, pick claims where students can produce their own proofs — equilateral triangles, the isosceles triangle theorem, the angle sum, and classification are all better candidates because students have seen the relevant proofs in school and can reconstruct them.

A good rule of thumb: if you are not fairly confident that students can produce a proof (even a rough one) within 10 minutes, either give them the proof or choose a different claim.