Part 1 of 4

Are Squares Rectangles?

By Madhav Kaushish · Ages 10+

What do you mean when you say a horse is a mammal or a square is a rectangle? Should we accept Aristotle's classification, where humans aren't animals, or modern biology, where humans are mammals? What basis do we use for such decisions?

The Dialogue Between Fliba and Lagard

Lagard: Fliba, my textbook says that a square is a type of rectangle. That doesn't make any sense to me. A square looks nothing like a rectangle!

Fliba: My teacher told me the same thing. She said it's because of the definition.

Lagard: But why should we just accept what the teacher says? Unlike names, which are chosen arbitrarily, mathematics should have logical reasoning behind its definitions.

Fliba: Fair point. Let's look at what the textbook actually says.

They examined the textbook definitions:

- A square is a quadrilateral with all sides equal and all angles 90 degrees

- A rectangle is a quadrilateral with opposite sides equal and all angles 90 degrees

Lagard: Wait — if a square has all sides equal, then its opposite sides are definitely equal. And it has all angles 90 degrees. So... a square does satisfy the definition of a rectangle.

Fliba: Exactly!

Lagard: But what if we defined a rectangle differently? What if we said a rectangle is a quadrilateral with opposite sides equal, all angles 90 degrees, and adjacent sides not equal? Then squares wouldn't be rectangles!

Fliba: That's true. So the answer depends entirely on which definition we choose. But which definition is better?

Enter Glagalbagal

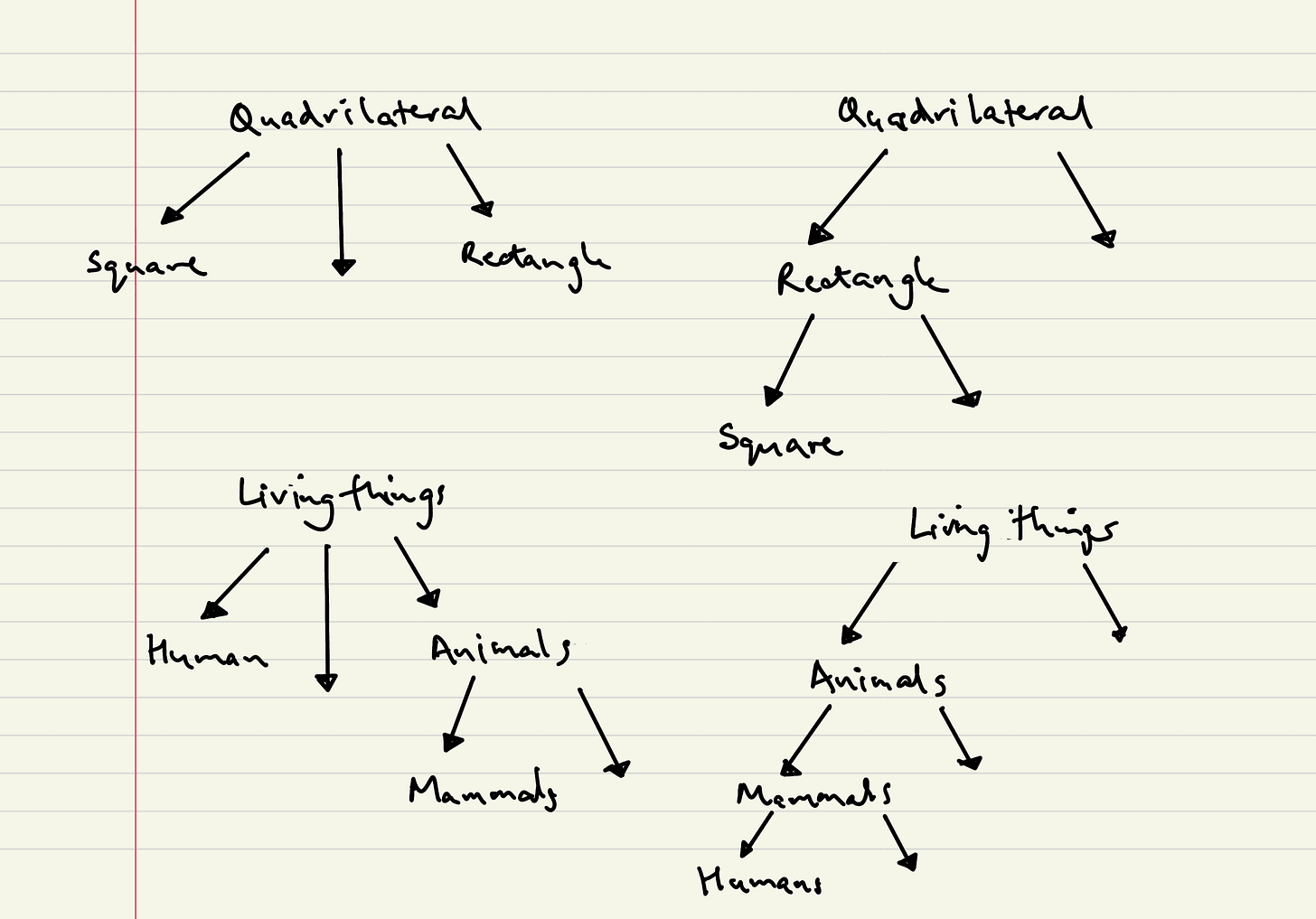

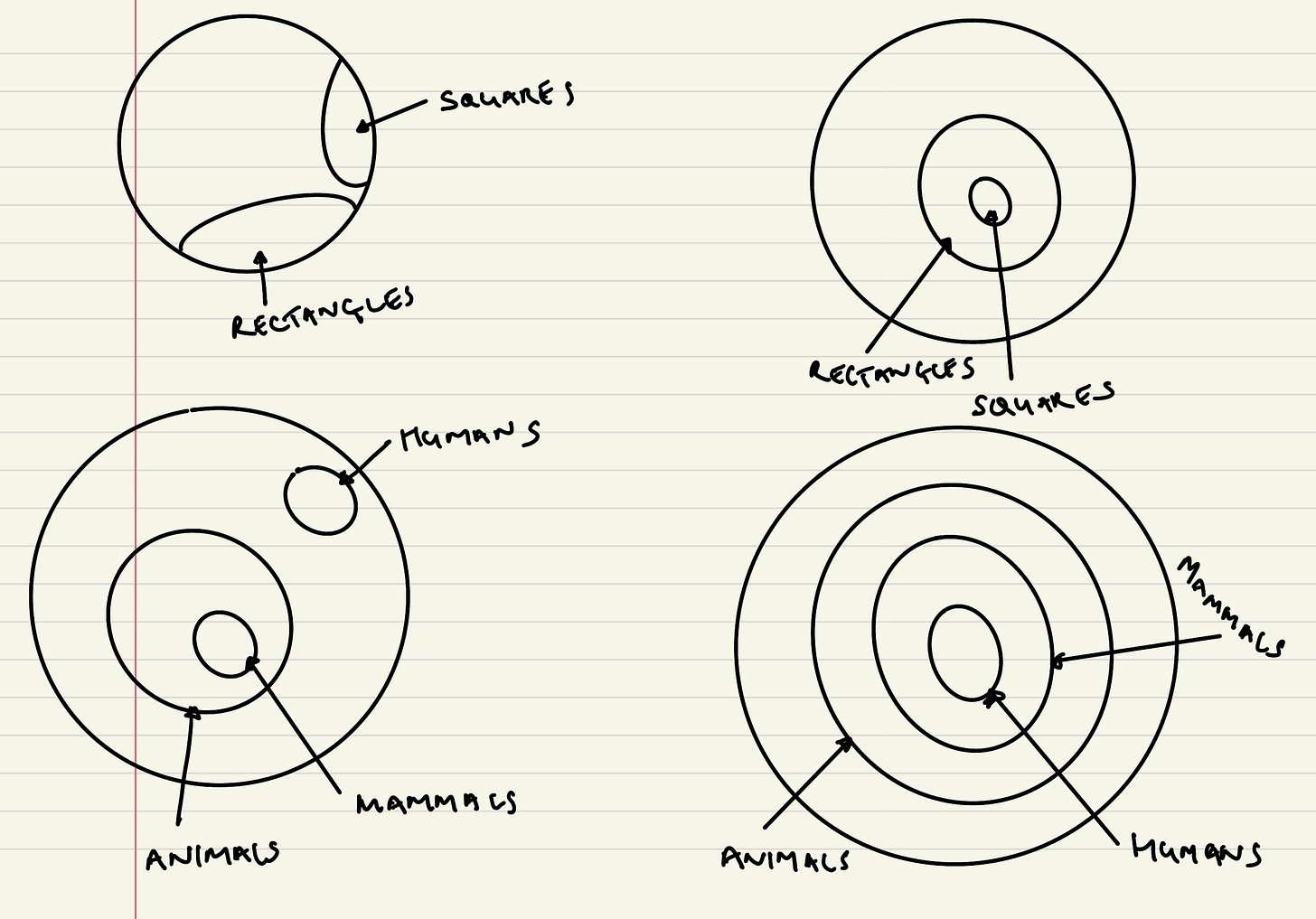

When they couldn't resolve this, they consulted Lagard's sister Glagalbagal. She introduced two ways of visualising classification:

Tree diagrams show hierarchical relationships using arrows to indicate "type of" relationships between shapes — just as you might show that a poodle is a type of dog, which is a type of mammal.

Venn diagrams use nested circles to represent the same categorical relationships — the circle of squares sits entirely inside the circle of rectangles.

Glagalbagal then challenged them to consider additional quadrilaterals — parallelograms, rhombuses, and trapeziums — to understand why certain classification schemes are preferred over others. She defined:

- A parallelogram as a quadrilateral with opposite sides equal

- A rhombus as a quadrilateral with all sides equal

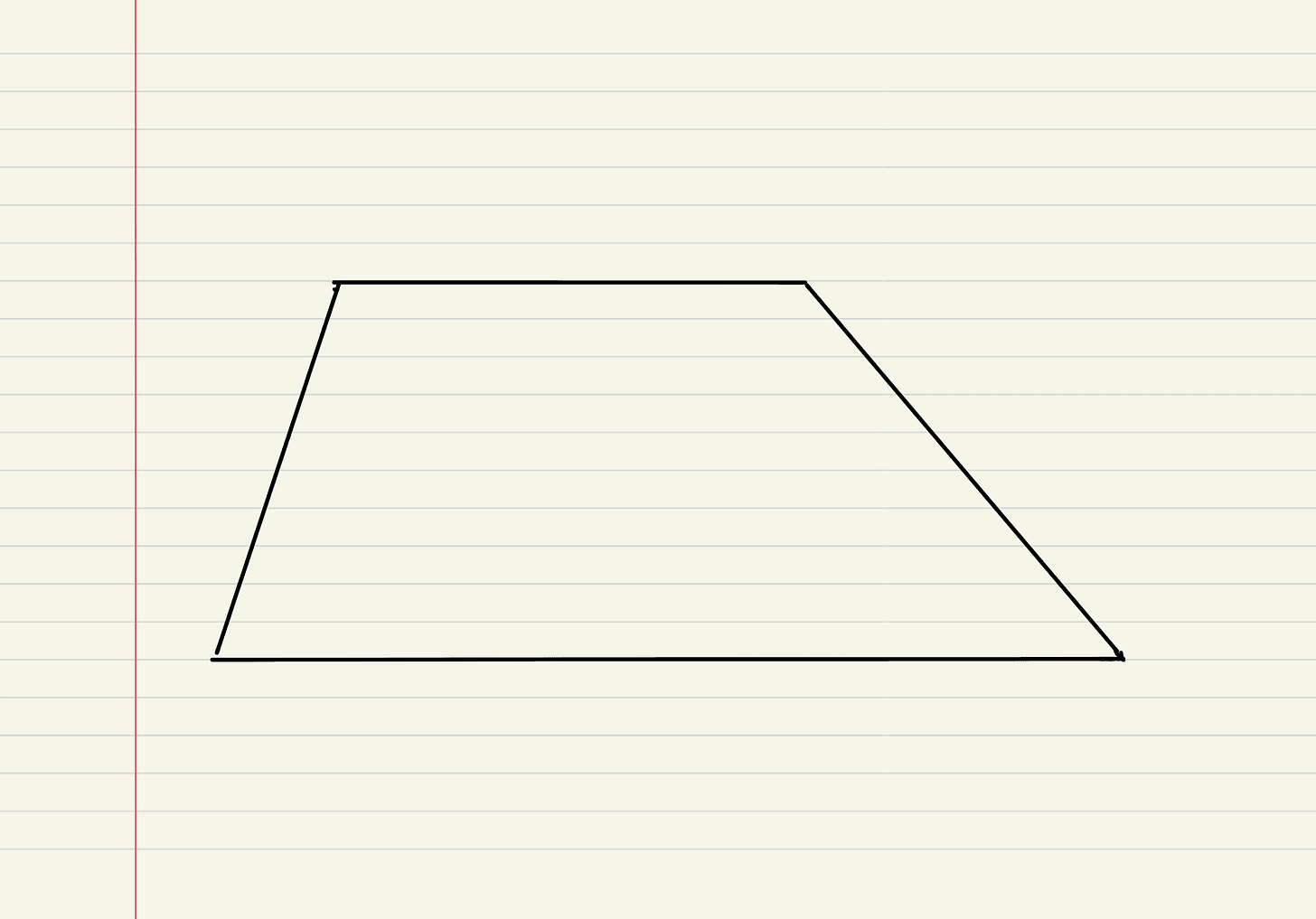

- A trapezium as a quadrilateral with one pair of opposite sides parallel